First was The London Review of Books shop, right on my corner, complete with its own tea shop and outdoor seating area, and home to a vast range of genres and book review quarterlies. (The London Review of Books is published fortnightly). I popped in three times over the course of the week.

In the opposite direction was the Atlantis Bookshop, an independent shop specializing in magic and the occult, tarot cards, incense, and various other related accoutrements. The shopkeeper, dressed in silky garb, with purple hair and a row of stars tattooed over her left eye, was having a conversation on the phone, and I happened to over hear a snippet: “If they had any sense at all they’d bask in your reflected glory and get on with it!”

Bookmarks, another shop in the immediate vicinity, specializes in left-leaning, social issue-focused, and occasionally radical texts. I noticed there were flyers posted in the windows for various social causes, and books by and for every racial minority, women’s issues, and so much more.

Venturing further out into London, I made a special trip west to Marylebone to find Daunt Books, perfectly catered to my taste for travel writing. If the collection alone wasn’t enough, the space itself boasts gorgeous oak architecture and an enormous vaulted skylight, making browsing their extensive selection of writing from and for every place imaginable even more cathartic with the sunlight streaming through. [Note: I experienced surprisingly good weather in London.]

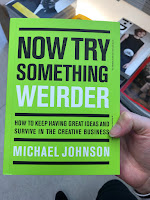

On Sunday, in the midst of a trek around the East London neighborhoods of Bethnal Green, Shoreditch, Whitechapel, and Spitalfields, in the boroughs of Hackney and Tower Hamlets, I sought out and stumbled upon a few more shops. Making my way southwest from the Columbia Road Flower Market, I wandered down a neat little side street covered in murals and found Artwords Bookshop. With books and magazines on contemporary visual culture, fine art, graphic design, and fashion, I felt as though I discovered a treasure trove. I slowly perused their selection, pouring over books about keeping things fresh as a graphic designer and how “selfie culture” and the infiltration of photography into our everyday lives has reshaped our perception of the world around us.

Later, I found Brick Lane Bookshop, which was unfortunately much less interesting than I’d expected, amplified thanks to the crush of crowds swirling around the market tents up and down the street outside. Down the block, I checked out Rough Trade East’s selection of pop culture related titles, and a table of casual reader’s staples inside Old Spitalfields Market.

One of my last stops was the famous Notting Hill Book Shop. Never having seen the namesake movie myself (I know, I know), I at first found it odd that a small group of tourists were taking turns snapping selfies in front of the shop, but soon realized what I was I missing when I spied a wall of film paraphernalia inside. The selection was fairly ordinary, and I was soon pushed out of the way by a delivery service dropping off a dozen boxes of books.

Honorable Mentions:

The massive Forbidden Planet London Megastore had the most extensive sci-fi/fantasy/manga section I have ever witnessed. I even made a video of it for Frank so he could witness the magnitude.

The last stop on my Muggle’s Tour of London (of course I booked that!) was in the middle of Cecil Court, the inspiration for Diagon Alley. Famous on its own for book shops, I counted seven: a few antique and rare book sellers, a children’s shop with a poster of the illustrated version of Harry Potter right in the window, and Watkin’s Books, longtime seller of spell books, among other things.